There are challenges to being a parent of adult children: They may not look or behave as we might want them to; our relationships can get testy; they may keep us out of the loop of their daily life and decisions. And yet there’s one constant we have: We love our children and want to keep them safe.

That struck me with force this week as I couldn’t stop thinking about the pain Alex Pretti’s parents are experiencing, to see the videos of their 37-year-old son–an ICU nurse who made a positive difference in his patient’s lives–murdered on city streets by government troops. No, let’s call them what they are, thugs hired and paid by our government.

- And then to have federal officials claim Pretti was a terrorist before an investigation had even begun!

- Even in their sorrow, his parents released a statement which included this line: “The sickening lies told about our son by the administration are reprehensible and disgusting.”

I have found it so relentlessly horrifying I hardly know how to keep from weeping for the Pretti’s, for Renee Good’s family (she was shot down a few weeks before Pretti was) and for the men, women and children snatched illegally from our streets and their homes. It’s disgusting and disheartening to live in a country that promotes and pushes such policies.

My apologies: I cannot keep politics out of this blog when I have even a limited platform to remind readers of the horrendous and callous events taking place on the streets of American cities–and how we, our children and grandchildren are at risk.

In search of some balance in these dark days, I turned to Nora Ephron’s “I Feel Bad About My Neck.” Her few sentences on the joys of grown children mixed with the never-ending concerns for their safety seem particularly relevant today.

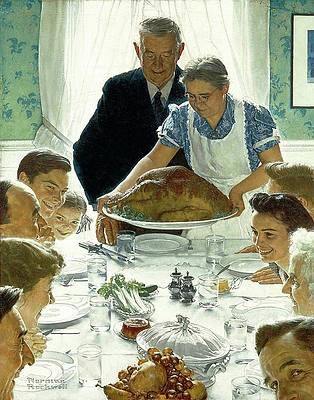

Every so often, your children come to visit. The are, amazingly, completely charming people. You can’t believe you’re lucky enough to know them. They make you laugh. They make you proud. You love them madly. They survived you. You survived them. It crosses youor mind that on some level, you spent hours and days and months and years without laying a glove on them, but don’t dwell. There’s no point. It’s over.

Except for the worrying.

The worrying is forever.”

photo credit: Maia Lemov